"Design & Disability" at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London

The creative action and artistic production of people with disabilities on display

by Marta Atzeni

It is rare for an exhibition to equally hold together the power of individual testimony and the scope of collective reflection on the meaning of design. Design and Disability, at the Victoria and Albert Museum (South Kensington) in London until 15 February 2026, fully achieves this goal: it not only tells the often overlooked contribution of disabled, deaf, and neurodivergent people to the world of design, but also invites visitors to rethink design, placing differences at the center.

Curated by Natalie Kane, the exhibition is divided into three sections – Visibility, Tools, Living – featuring a total of 170 objects ranging from technology to architecture, from graphics to design, from photography to fashion. Although the selection spans from the 1940s to the present day, it does not aim to trace a systematic history of the relationship between design and disability, but rather to show the variety of its expressions and the plurality of its protagonists, the creative power, and the deep connection with social justice practices.

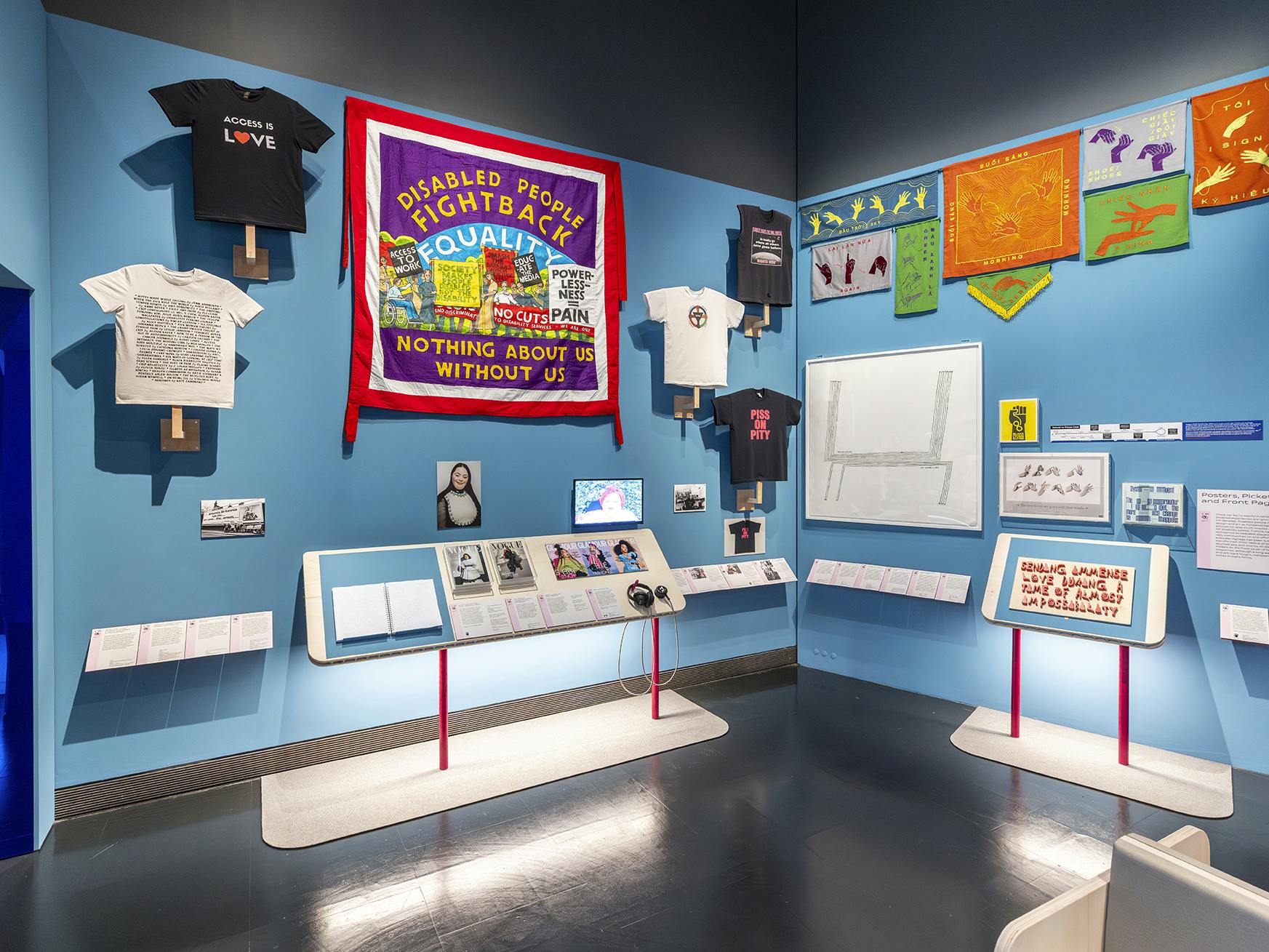

The first section, Visibility, celebrates the expression of disabled identity and culture. In addition to famous examples where design has been a tool for awareness campaigns and fights for rights, such as the poster The best lovers are good with hands by AIDS Ahead and the iconic t-shirt PISS ON PITY, the section opens a window onto the world of self-published magazines and podcasts. Comfortably seated on a padded bench, visitors can browse zines and listen to podcasts, produced by and for disabled people, which serve as essential platforms for expression and community. Alongside these forms of contemporary activism are examples of self-determination from the fields of fashion and photography: from the hats to the flamboyant corsets of Sky Cubacub, which claim full agency for bodies and identities excluded from dominant narratives, to the joyful self-portraits of Marvel Harris and the glimpses of daily life during Covid by Jameisha Prescod.

The focus is on design Tools. Challenging the view that reduces disabled people to passive users, the second section of Design and Disability presents an anthology of small and large 'hacks' demonstrating how necessity, far from being a limitation, is often the source of radical innovations. Designed by Microsoft together with disabled gamer communities, the famous Xbox Adaptive Controller is displayed alongside clever low-tech solutions conceived by Cindy Wack Garni to regain the ability to perform simple daily actions after becoming disabled in adulthood. There is also the Touchstream touchpad, created by engineer and Fingerworks founder Wayne Westerman to alleviate his hand pain: a device that, using sensors to track movements, replaces the traditional keyboard. Initially marketed for people with motor difficulties in their hands, the invention was acquired by Apple in 2005, which incorporated its functions into the first iPhone, revolutionizing the tech industry.

The creative action of disabled people influences not only the innovation of tools, but also the transformation of the built environment and the systems governing it. Living, the exhibition's final section, recounts the battles for accessibility and the role of design in this process. Public S/Pacing, by Helen Stratford, is a blanket designed for resting in public spaces, whose embroidered writings denounce design deficiencies by challenging ableist logics. The Grove Road Housing Project in Nottinghamshire, England, designed by activists Maggie and Ken Davis in 1976, is the first example of social housing that enabled independent living for wheelchair users. SEALAB, instead, is a school for blind and visually impaired children in Gujarat, India, designed with particular attention to sensory navigation: different textures along walls indicate changes in room function, while the various scents of aromatic herbs signal the presence of courtyards. Also on display is Signstrokes, a new vocabulary developed by architecture students Adolfs Kristapsons and Chris Laing, introducing architectural terminology into sign language.

While the projects on display offer a powerful and layered narrative, the space that hosts them is no less significant. At the entrance to the gallery, a welcome area greets visitors with a video in British Sign Language (BSL), while a tactile map and audio description aid orientation. Throughout the route, punctuated with rest stations, tactile surfaces and flooring mark the presence of cases, platforms, and display tables set at accessible heights. A decompression zone, with furniture and objects designed by occupational therapists, concludes the visit. A manifesto of accessibility and inclusivity, reinforced by the presence of informational materials offered in different levels of linguistic complexity and formats: tactile panels and captions, large print paper guides, audio descriptions, and video tours in BSL.

Showing, in the sanctuary of applied arts, that what disables people is not their condition, but rather the political, environmental, and behavioral barriers of society, Design and Disability invites professionals, students, and others to rewrite the grammar of design. Only by radically redefining inclusion, agency, and normality is it possible to develop genuinely responsible design practices and chart new courses for the design of the future.